SOE EduTalk: "The Negotiations of Pakistani Mothers’ Agency with Structure: Towards a Research Practice of Hearing ‘Silences’ as a Strategy"

Aliya Khalid was our speaker in the fourth online session of the EduTalk series of Spring 2022. She spoke about “The Negotiations of Pakistani Mothers’ Agency with Structure: Towards a Research Practice of Hearing ‘Silences’ as a Strategy” on Friday, April 08, 2022, from 3pm till 4pm. The session was moderated by our own Dr. Tayyaba Tamim (Director Academics and Faculty) from Syed Ahsan Ali and Syed Maratib Ali School of Education, LUMS.

The Negotiations of Pakistani Mothers’ Agency with Structure: Towards a Research Practice of Hearing ‘Silences’ as a Strategy

Research shows that in Pakistan daughters of educated mothers are likely to be enrolled in school, thus proposing a decontextualized relationship between mothers and their daughters’ education. This paper draws on interview data to narratively analyse the situated experiences of Pakistani mothers for supporting their daughters’ education. When mothers’ life stories are analyzed, a lifelong strategy of silences is revealed. Through the construct of silences, Aliya challenges herself and other educational researchers to ‘unlearn’ the hegemonic epistemic cues that bind us to certain ways of knowing and instead develop a critical openness to the perspectives of mothers and become ‘hearers’. This paper situates itself within the debates on epistemic justice – proposing a practice of critical ‘hearing’ to understand the lifelong situated experiences of mothers in Pakistan.

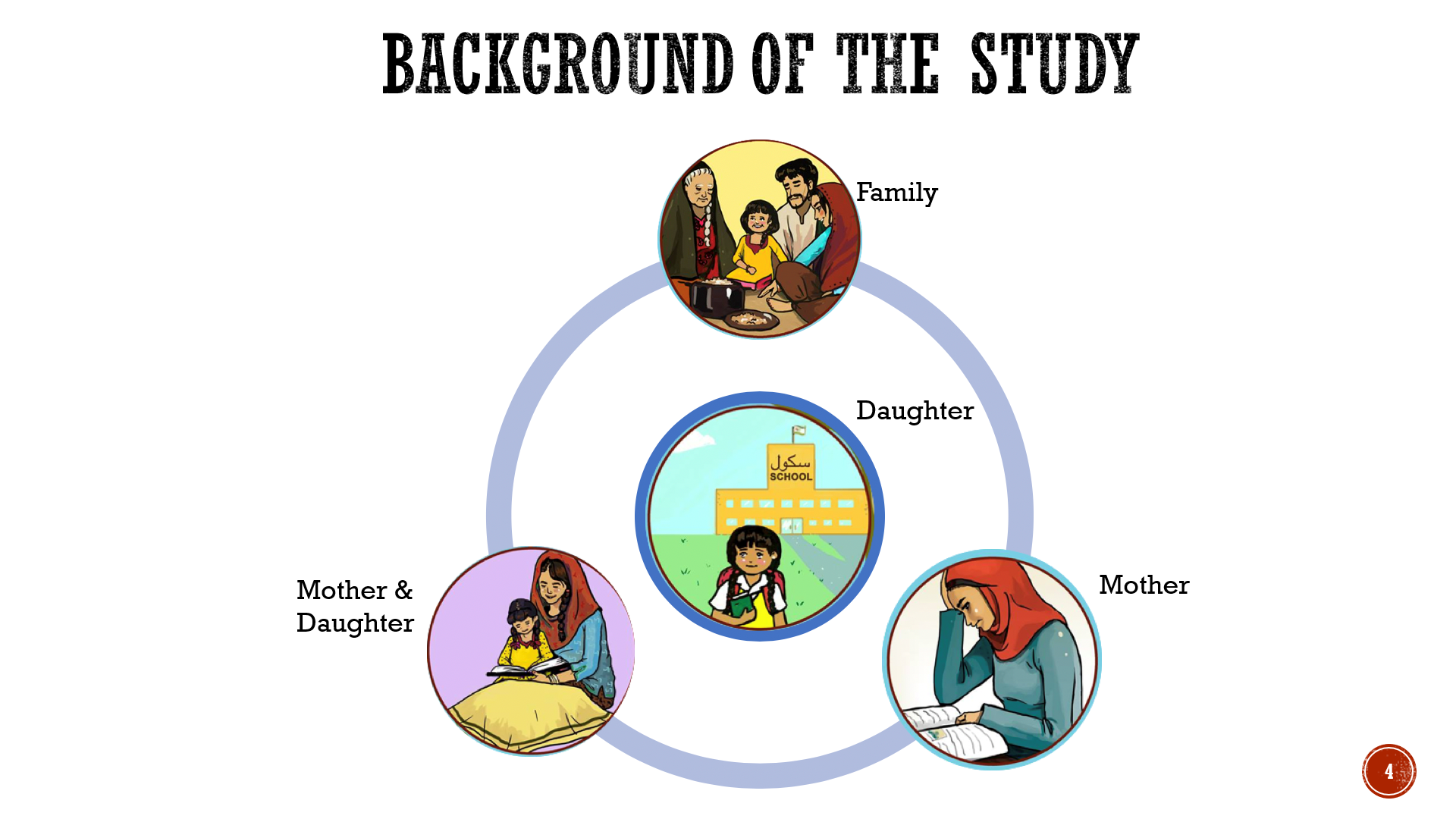

The approach to her study formulates from understanding her own limitations and understanding her own personality as well. She mentions that perception and positionality is especially important to address issues of education in a household where female are present. The background of her study focuses on developing economies contexts including Pakistan, where she finds that there is a positive relationship between mothers, and their daughters’ education. She focused on the relationship between the mothers and their daughters and how that capability of the mothers enables or hampers the development of their daughters’ education in the rural communities of central Punjab in Pakistan. These studies mostly focus on attributes, such as mothers’ education and autonomy. While the intricate process of mothers’ influence remains less explored, she has adopted a very human capital approach.

For her research, she posed a few important questions and themes to help her gather the data for the study:

- How do mothers shape their daughters’ education in rural Punjab Pakistan?

- In the broader project, thirty mothers and their family members, were interviewed from the same neighborhoods in three different rural communities in central Punjab.

- Semi structured interviews were developed drawing on the capabilities approach and data was collected for a qualitative study.

- Conducted thematic and narrative analysis of mothers’ stories

Drawing on certain ideas from the capability literature, she identified two things – Aspirations and Actions which mothers typically performed. These were both concrete and vague aspirations, which the mothers expected from their daughters. This was drawn from the past matters in the family and motivated from the future aspects which the mothers and daughters can achieve. They talked about various aspects e.g., what they expected out of education for their daughters? If education is considered a valuable thing for their daughters? And harms which education can bring to their daughters.

In order to understand the mother’s role, Aliya compared mother’s aspirations to various actions which the mothers were performing. She also explained the difference between ‘Aspirations’ and ‘Actions’ generally and in the context of mothers’ roles as:

- Aspirations: ‘The notion of aspirations can be vague, from dreams and fantasies to concrete ambitions and goals. Aspirations, however, usually connote the achievement of something high or great. They also address both present and future perspectives (Gutman and Akerman,2008, p. 2)’

- Actions: to support their daughters’ education

This study focused not only on the current time period but was spread over the course of motherhood and the impact of the mother’s aspirations and actions on the daughters over a large span of time.

While on the field, Aliya discovered new facets of the problem, and recognised it as Miranda Fricker calls it a ‘Moment of Epistemic Revolution’ where she thinks that we come with preconceived notions and judgment and view the problem with our lens of predisposed understanding. Meanwhile the reality would be much farther from that and there are things happening which do not make sense to a fleeting eye. Here, she found out that most women were abiding by the gender roles and norms of the society and culture. However, there were a few triggering points which propelled these mothers to go an extra yard and have ‘extraordinary’ or simply ‘different’ aspirations for their daughters.

Aliya also came across some research by Saba Mehmood, who had worked in Egypt and had worked with women’s organizations which were active during the Islamic Revival Movement in the country. Aliya found that Saba’s research had similar cases. However, the latter’s studies found women to be challenging these restrictions in some powerful ways. According to Aliya, Saba produced the idea of agency which she says should be open-ended. She mentioned that agency was important in maneuvering through the various obstacles which the society, cultures and norms presented to these mothers and how the women used this agency for their own and family’s benefits.

It was obvious throughout that the mothers who were educated themselves considered education as a priority for her daughters and learnt that Agency was particularly important while making these important decisions amongst the families. She explained Agency as:

- Agency: ‘agency …as a capacity for action that historically specific relations of subordination enable and create. This relatively open-ended understanding of agency…[explores] those modalities of agency whose meaning and effect are not captured within the logic of subversion and resignification of hegemonic norms (Mahmood, 2006, p. 34)’

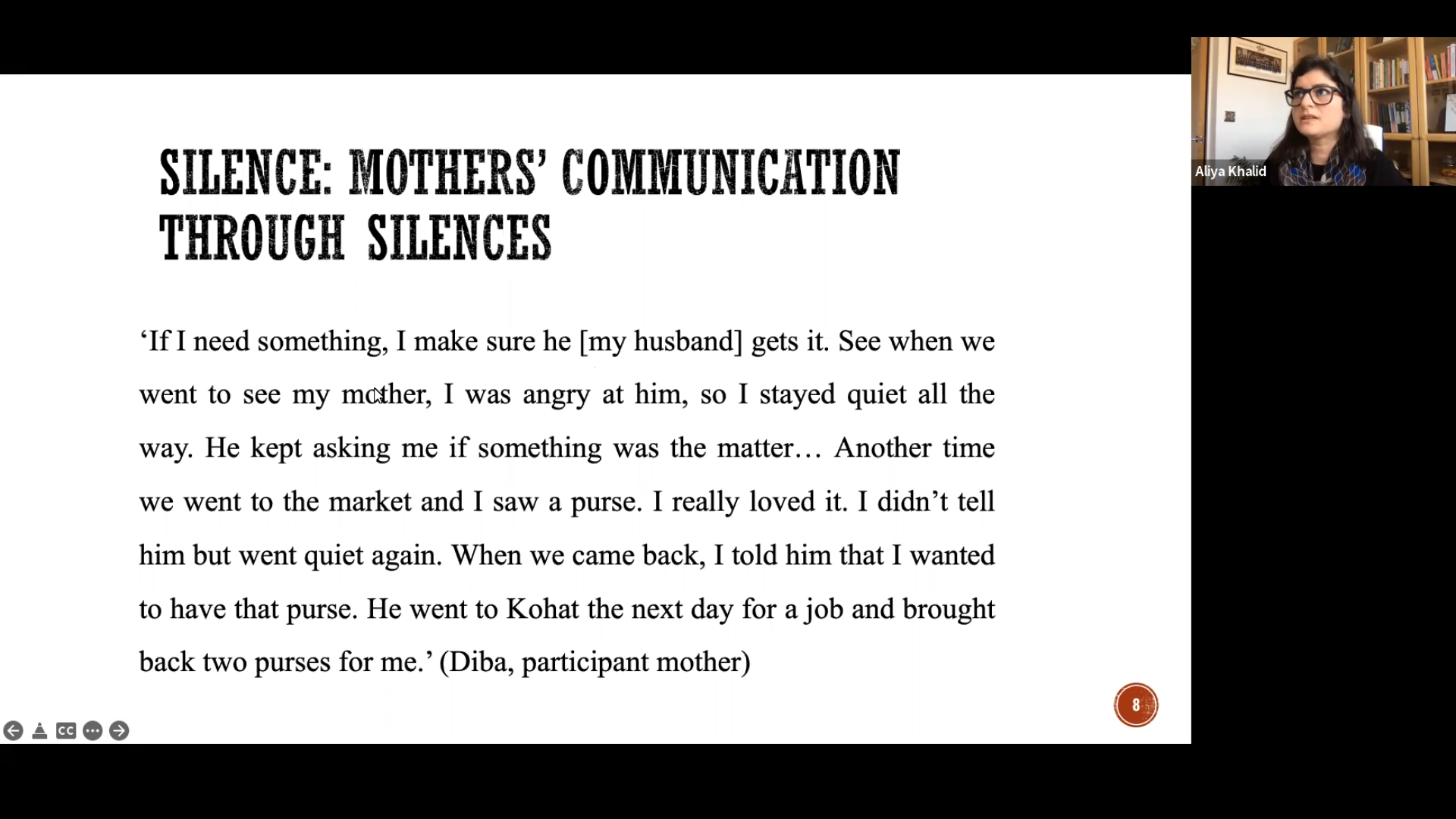

She also explained that where there are relationships which exist in the subordinate form for women, there the women surprisingly find intelligent forms of agency and make use of that. In one case, she explained that in certain cases and households, women will use ‘Silence’ as a form of decision making and showing their affirmations or rejections in a decision. Aliya believes that there is an element of critical openness with the researchers, practitioners, and policymakers. Here, the idea is to understand the limitations of our own knowledge and experiences while assessing problems and have those epistemic revolutions when they are eventually arrived at. Instead of considering ‘silence’ as violence, a few scholars believe that it should be considered a paradoxical concept and mode of getting what the subjects want. Hence, it should not be considered as a form of violence but a way of expressing certain things. Here Aliya explains, “Silence is not a heroic condition and is paradoxical and a little bit ambiguous, therefore, as a researcher we are understanding paradoxicality of silence and voice and breaking out the binary.” She also uses ‘silence’ in a figurative sense, for example one who does not want to talk about something and a withdrawal of voice, action and aspiration and refusing to express. This created a situation of disengagement, refusal and re-engagement enigma which went on throughout the lives of these mothers who knew the number of options they had versus their aspirations.

At the end of the day, these methods did eventually get the mothers their nearly desired results. Since, the method of silence was used very often, the daughters also picked up on their mother’s behaviour and employed the same in their dealings with the family heads. This was an ingenious way of breaking away from the norms. So, in the face of so many issues, while we challenge patriarchy, we also need to take into notice the intersectionality, the economic barriers, and problems plus the security issues for females in the country. What Aliya found was that many struggles happen simultaneously on many varied fronts for these women, and as scholars it is important to recognize and understand those struggles while we view the overall issue.

In conclusion, Aliya calls to researchers and practitioners to be critically reflexive and recognise the limitations of the knowledge which they bring with themselves to the research contexts and to practice ‘critical openness’ to the word of others, as Fricker mentioned. She mentions that Fricker views this dilemma as ‘Epistemic injustice’ where we as a scholar, do not give enough credit to the speaker and people as we do not see them as knowledge producers. This way, our deductions are mostly based on our own preconceived judgments and not completely based on what the subject or the speaker is sharing with us.

Further in conclusion, she says, her paper is a critique on herself as a researcher and scholar. While talking about knowledge production and representation, Aliya referred to the work of Boaventura de Sousa Santos who talks about Globalization and the global north (western Europe essentially) and he says that they are mired with epistle thinking which means that this global north draws a very strict boundary between ‘their’ knowledge and the ‘other’ knowledge.

Hence, the description of ‘their’ knowledge is linked with ‘self’ which is considered ‘superior’ and the ultimate knowledge which needs to be recognized hence creating epistemicide. Hence, the ‘others’ knowledge is not allowed to enter the ‘self’ knowledge, which creates a myopic vision of any study. This becomes an issue of perception management for any problem as well. Finally, Aliya says that there are ways which form disconnection from the knowledge which is coming from the subjects and how they are rendered by the scholar/researcher. In her paper, Aliya critiques herself and her work and encourages her peers to be aware of these epistemic issues and recognize their drawbacks.

About Aliya Khalid:

Aliya teaches on the Comparative and International Education MSc programme at the Department of Education at the University of Oxford in UK; after having taught at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge. Her research focuses on how women in the South navigate their agency in highly constrained circumstances. Her specialised areas of interest are the capability approach, negative capability, epistemic paradoxicality and justice, and the promotion of knowledges (plural) and Southern epistemologies. Aliya actively engages in issues around the politics of representation and knowledge production in the academe. Aliya is currently accepting doctoral students with an interest in these areas.

Profile and other works can also be found here.

About Dr. Tayyaba Tamim:

Dr. Tayyaba Tamim is currently an Associate Professor and the Director of Academics at the Syed Ahsan Ali and Syed Maratib Ali School of Education, Lahore University of Management Sciences. She is the Faculty Lead of the Pedagogical Partnership Programme at the LUMS Learning Institute. She has her PhD from University of Cambridge as a fully funded RECOUP scholar and MPhil RSLE (Research in Second Language Education Across Cultures) from Cambridge, UK as a British Council Chevening scholar. Dr. Tamim has led several funded research projects with national and international partners, including with USAID, British Council, and the World Bank. She has also published and presented research papers at several national and international forums. Her work covers issues of social justice, equity, and inclusivity in education.

About EduTalk:

EduTalk is an exclusive series of guest speaker sessions by the School of Education (SOE) at LUMS, where various topics in educational research field are discussed by seasoned professionals from across the globe.